Kafka is, without a doubt, a fancy and hyped piece of technology that powers communication between different systems at massive companies. In this post, I’ll explain the inner workings of Kafka for someone who has never used it before (like me), by breaking down the architecture of this impressive platform.

The problem that powered the creation of Kafka

To understand how Kafka works, it’s helpful to understand the limitations that necessitated its creation. It boils down to one simple concept: scale. When you have different services at a company that need to communicate, you must architect them in a specific way to handle growth.

As an example, let’s imagine we are a search engine platform. We need to track the performance of sponsored results for multiple reasons:

- Service B (Billing): Needs to know how many clicks each sponsored result received to charge the customer.

- Service C (Metrics): Needs to aggregate data to display on the customer dashboard.

- Service D (Search Quality): Needs to know which result the user clicked to determine if it was a good fit for the search terms.

The simplest solution (without using messy workarounds) is to manually call each service whenever we receive a “result clicked” event. We call Service B, Service C, and Service D using HTTP.

- If we wait for the response, the request takes too long, and we fail the entire operation if one service is down.

- If we don’t wait for the response (fire and forget), we risk losing data if one of the services is down or slow.

Even if each service has a load balancer routing requests to the least used instance, this approach is far from ideal. Beyond the latency risks, the endpoint triggered when a user clicks a result now needs to know about three other services. If we later launch a new Service E (e.g., to track time-to-click), we have to update our endpoint code to call that new service.

There are too many points of failure and too strictly coupled information. This complexity exists with a simple 1 producer / 3 consumer situation. You can imagine how unmanageable this becomes when you are Google, LinkedIn, or Uber.

To resolve this, engineers created a concept where you push events to a log and stream them to everything that needs to do work around that event. This motivated the creation of Kafka. In the next section, we’re going to understand in-depth what Kafka is and how it fixed the mess of event streaming at scale.

Building the tool

The method that helped me understand Kafka the most was imagining building it from scratch, step by step, and stressing it to see where it breaks. Let’s start that journey.

Starting simple

First, we can create a linked list in memory where we insert events and perform read operations. We create a TCP protocol interface to let services programmatically insert records into that list and read them.

Now we have a tool to send events from one service to another. Service A sends “User X clicked on result Y at time Z,” which gets added to the list. Service B polls that list every 5 seconds to check for new events. Once Service B sees a new item, it reads it, processes it, and keeps a reference to the last message it read.

This gives us an immediate benefit: Backpressure. Service A can push messages at any speed, and the consumer (Service B) processes them as fast as it can without losing data or getting overwhelmed by the traffic spike.

This solution works… until it doesn’t. The main issue is that the list will grow forever. Service B will have more bytes to read every time, and the RAM usage of our tool will grow until it crashes, causing total data loss.

Offload to the disk

To solve the RAM limitation, we can append every received record to a file (yes, a simple text file) instead of keeping it all in memory.

log.txt:

User x clicked on the search result y at time z

User a clicked on the search result b at time c

If we just write/read from that file, we aren’t constrained by RAM size. While disk I/O is slower than RAM, we can mitigate this using a mix of both. We keep active data in RAM (using OS page caching) and offload to the disk for persistence and storage. Because we are appending sequentially, disk write speeds are actually quite fast.

Keeping state (Offsets)

One issue with our current strategy is that a simple “read” operation is inefficient if it always returns the entire list. Previously, we were lazy and didn’t implement a way to fetch specific records. We can improve this by implementing an offset tracker.

We change our protocol to use next and commit_offset operations instead of a bulk read:

- next: Gets the next event (or batch of events) in the list after the last known offset.

- commit_offset: Updates the current offset of the list to a specific position.

Every time we call next, we get just the new data. After processing, we commit the offset. Now, if our consumer crashes and restarts, it resumes processing exactly where it left off. Furthermore, the server can now operate faster by keeping only the “active” segment of records in RAM, leaving older data on the disk.

Distribution

Now our application is scaling. Service A is pushing events so fast that Service B can’t handle them in time, causing a growing delay (lag). Our single instance of Service B can’t advance the offset as fast as new events arrive.

We can’t simply run a second instance of Service B because they will fight over the offset. They would end up processing messages twice or skipping them entirely due to race conditions.

To fix this, we need to distribute records evenly between the two service instances. Let’s look at solutions we don’t want:

- Commit on receive: If the service commits as soon as it grabs the record but crashes during processing, that data is lost forever.

- Load balancing reads: If the server tracks “Instance 1 has message #4, so give message #5 to Instance 2,” we lose guaranteed ordering. Event #5 might finish processing before Event #4.

The best solution is Partitioning.

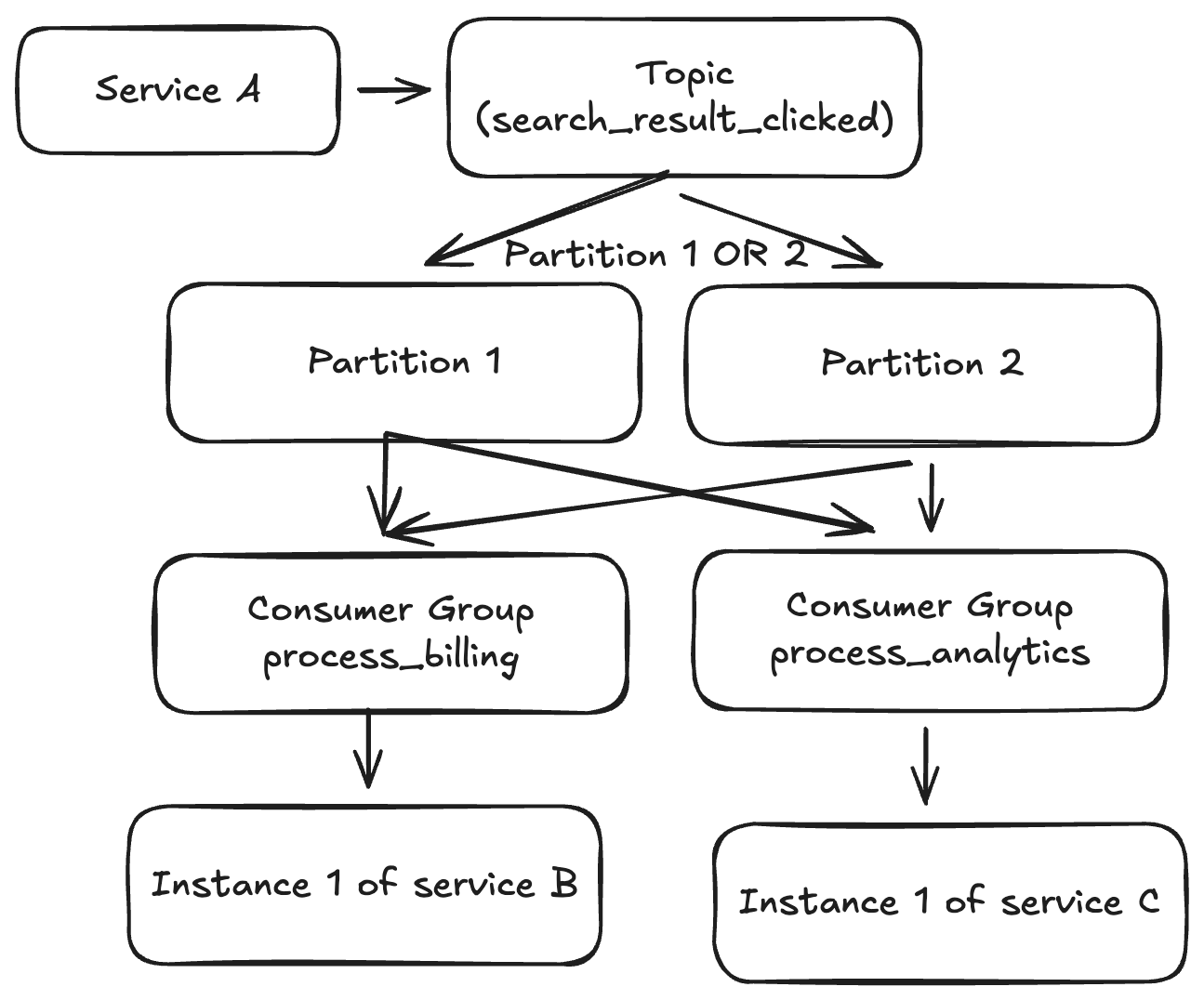

Partitions are subsets of the events. We can look at the content of an event (e.g., the User ID) and use a hash algorithm to decide if it belongs to Partition 1 or Partition 2.

- Fast insertions: We are still just appending to files.

- Low footprint: We only track the last offset per partition.

- Independent processing: Because we force each partition to be consumed by at most one instance, we guarantee that events in the same partition are processed in order.

If we use userId as the partition key, all events for that user fall into the same partition and are processed sequentially. At this point, you would be surprised by how close we are to Kafka.

Topics

Our solution worked well for Service A → Service B. Now we want to use it for Service K → Service L. Currently, all events go into one giant log.

We need Topics. A Topic is simply a logical grouping to ensure different communication paths don’t interfere with each other. Each topic can have multiple partitions for scalability. Now we can use this platform for as many services as our hardware permits.

Broadcasting events (Consumer Groups)

We still have one gap. Remember that Service A sends an event that needs to be consumed by Services B, C, and D? We don’t want to create separate topics for every destination, or we are back to the coupling problem.

We introduce Consumer Groups.

Instead of instances reading directly from topics, instances belong to a consumer group. The group reads from the topic. The offset is now tracked per Consumer Group.

- Service B Group: Tracks its own offsets on the topic.

- Service C Group: Tracks its own offsets on the same topic (independently).

This allows us to broadcast one event to multiple consumers. Inside a single group (like “Billing Service Group”), we can have multiple instances to increase parallelism. Kafka ensures that a partition is assigned to only one instance within that group to maintain order.

Service A now does just one thing: Sends the event “User X clicked result Y.” It doesn’t know who is listening. This scales incredibly well.

Replayability

A massive side-effect of this architecture is the ability to replay history. Remember the append-only log file? We aren’t deleting items immediately after consumption. We have an immutable history (based on retention policies).

- New Features: If we create a new Service E, we can start its consumer group at offset 0. It will read all historical search events and populate its database from scratch.

- Bug Fixes: If we deploy a bug in Service B, we can fix the code, reset the offset to a time before the bug appeared, and replay the events to correct the data.

The last missing part: True Scale

So far, our limit is the CPU, RAM, and Disk I/O of a single machine.

Napkin math: If we are Google processing 16.4 billion searches per day, that’s roughly 190,000 events per second. If a payload is 1KB, that’s ~185 MB/s or 1.5 Gbps. If we have 1 producer and 3 consumers, that network load quadruples. We will hit physical limits quickly.

The solution is Clustering.

Since we already have an algorithm to distribute events across partitions, we can distribute those partitions across multiple servers (Brokers). The brokers communicate to decide who is responsible for which partition. If we send an event to the wrong server, it forwards it to the right one.

Now, the server specs are not our limit. We can also replicate data across multiple servers for high availability. If one server burns down, another has a copy of the partition and takes over.

The Kafka Ecosystem

Now that we’ve built the mental model, let’s define the actual Kafka terminology.

Broker

A Broker is a single physical or virtual server. It is part of a cluster where it stores specific partitions and handles replication.

Partition

A Partition is an append-only log of records. It guarantees order. A topic is split into multiple partitions, which allows the topic to scale across multiple brokers.

Topic

A logical category for messages (e.g., “user-clicks,” “orders”). It is composed of one or more partitions.

Consumer Group

A logical grouping of consumers working together to consume a topic.

- Each partition is assigned to at most one consumer instance within a group.

- One consumer instance can handle multiple partitions.

- This ensures parallel processing while maintaining order per partition.

Consumer

The actual server/application instance reading data.

Key Features

Rebalancing

Kafka is smart enough to rebalance partitions across a consumer group. If a consumer instance dies (times out), Kafka detects this, removes the consumer, and reassigns its partitions to the remaining healthy consumers automatically.

Replication

For durability, you can configure replication. A partition has a “Leader” (where writes happen) and “Followers” (passive replicas). If the Leader broker fails, a Follower is promoted to Leader, ensuring no data loss.

Offset Committing strategies

- Auto-commit: Great for throughput. The offset is committed periodically. If the consumer crashes, you might “lose” the processing of the last few messages (they were marked read but not processed), or process them twice depending on the timing.

- Manual commit: You commit the offset only after your logic runs successfully. This guarantees “At Least Once” processing but requires careful coding to handle duplicates.

“At Least Once” Delivery

It is vital to understand that Kafka generally guarantees At Least Once delivery.

- Consumer A processes a message.

- Consumer A crashes before committing the offset.

- Kafka rebalances.

- Consumer B gets the partition and reads the “uncommitted” message again.

Your application logic must be idempotent (handling the same message twice shouldn’t break your database).

The “Stuck Partition” (Poison Pill)

If a specific message payload causes your consumer code to crash (e.g., a regex error on a weird character), the consumer will die without committing the offset. Kafka will reassign the partition to another consumer. That consumer reads the same message and also crashes. This can block the entire partition.

Handling this requires “Dead Letter Queues”—catching the exception, moving the bad message to a separate topic for manual inspection, and committing the offset so the partition can move on.

Kafka is not a Queue (and why that matters)

A traditional Queue (like RabbitMQ or SQS) implies:

- Records are deleted after processing.

- The queue tracks the state of every individual message.

Kafka is an Event Stream.

- Events are stored persistently for a retention period (e.g., 7 days).

- The broker keeps no state per message. It only tracks the offset (an integer) per consumer group.

Because Kafka doesn’t track per-message state, it doesn’t need to perform random I/O on the disk. It utilizes sequential I/O, which is incredibly fast.

Log Compaction: Kafka as a Database?

Kafka can act as a source of truth. With Log Compaction, Kafka keeps only the most recent version of a message for a specific key.

Sequence:

User A: { name: "Pdro", active: false }User A: { name: "Pedro", active: true }

Eventually, Kafka deletes message #1 and keeps only message #2. This allows you to “rehydrate” a database table by reading the topic from the beginning, as it effectively stores the final state of every entity.

Modeling Systems

When modeling for Kafka, remember you are dealing with streams, not tables.

Topic Naming Examples:

- user-updates: When a profile changes. Consumers update S3, SQL, and caches.

- orders-placed: When a user checks out. Consumers trigger fraud checks, inventory reservation, and payment processing.

Payload Best Practices:

- Keep it thin: The default max size is 1MB. Don’t send PDFs or videos. Store the file in S3 and send the URL/ID in the message.

- Schema Registry: Use a schema registry (like Avro or Protobuf). If you change the payload format, you don’t want to break downstream consumers who are expecting the old format.

Metrics and Scale

To give you a sense of scale, here is a quote from LinkedIn (the creators of Kafka):

“We maintain over 100 Kafka clusters with more than 4,000 brokers, which serve more than 100,000 topics and 7 million partitions. The total number of messages handled by LinkedIn’s Kafka deployments recently surpassed 7 trillion per day.”

— Jon Lee, LinkedIn Engineering Blog

For most non-Big Tech use cases, tools like RabbitMQ or Redis Streams are sufficient. Throughput usually becomes a bottleneck only when you surpass ~20k messages per second or strictly require the persistence/replay features of Kafka.

Conclusion

Kafka is a fascinating system designed for workloads that most other platforms simply cannot handle. Beyond its market dominance, it employs brilliant engineering solutions for persistence, routing, and availability.

It is a complex beast—it took me a week just to grasp the basics. But asking questions like “What about retries?” or “What if the consumer fails?” drives you to a deeper understanding of distributed systems architecture.